The Interstitium

What a “new” body part can teach us about the value of systems understanding

You may have already read about or heard this news, but in case you haven’t, let’s get you up to speed on something that, for many of us, is mind blowing: Western medicine recently discovered a “new” human body part. Of course it’s not new, as it has always been there, but it was only identified by Western scientists recently. And it’s not just any new body part, but one that some consider to be an organ. While it needs large-scale agreement across the medical field to “officially” be called an organ, it is certainly a distinct anatomical system, one that connects all other organs and that contains more fluid than any other in our body. In fact, it contains more fluid than the volume of our blood.

Meet the interstitium.

Yes, you read that correctly. This (possible) organ was sitting in plain sight but somehow was unknown to Western medicine for a really, really long time. How did we miss this? Why did we miss this? Why does it matter? And what can our overlooking of the interstitium teach us about the value of systems thinking and systems understanding in social and environmental change?

THE DISCOVERY

Before exploring how we got here, let’s go back to the “new” body part and review its properties. The interstitium is an interconnected channel of fluids that is under our skin and lines every organ, as well as our arteries, veins, nerves and fascia between muscles. Western medicine had previously identified interstitial fluid, the fluid between the organs and other body parts, but prior to this “discovery,” we hadn’t understood that this fluid traveled through a lattice-looking network, connecting organs with a system that allows for communication and transfer of fluid without the use of the blood stream.

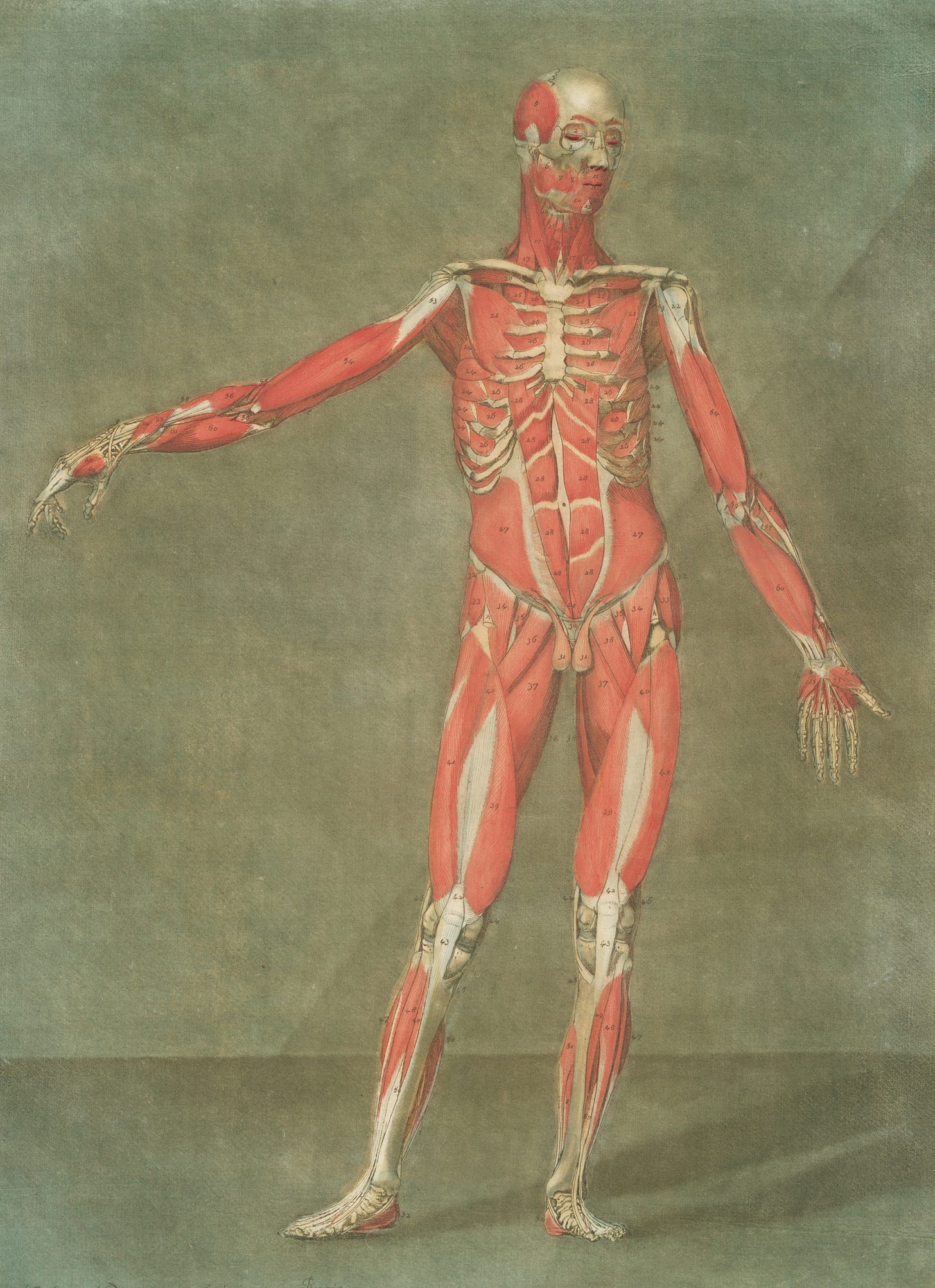

Photo by The New York Public Library on Unsplash

The story goes something like this: In 2015, using a technology called in vivo microscopy, Neil Theise, a medical doctor and professor of pathology at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, noticed what looked like a web of tubes on the surface of the bile duct. He reached out to colleagues with inquiries about the existence of this lattice-like network, which his training had taught him was not supposed to be there, and was met with skepticism that such a discovery was plausible. His peers were probably thinking, “How could we have missed something like this?”

Despite this skepticism, he dug further, and he not only found it on the bile duct but on every other organ he checked. At first it seemed like this could be labeled scientific discovery only made possible due to new advanced viewing technology, but as it turns out, the interstitium is actually visible to the human eye. It was visible all along, yet somehow, we missed it.

Our missing it has a lot to do with a culture of linear practices, those overlooking complexity, such as how we tend to break things up into parts, rather than look at the whole. We think if we can just break things down into smaller and smaller bits we’ll be about to figure out the nature of the whole – but that is not how complexity works. There are emergent qualities that only come out when a systems is viewed in totality. For example, examining a heart on its own, or some lungs, can teach us interesting and important things about human life, but they are not alive on their own. It’s the complete system, where the circulatory system meets the nervous systems (meets the interstitium system!) and more, that all connect and create the emergent property we call being alive.

In this case, the act of literally dissecting something meant we lost the big picture of the whole. When an organ is cut out and preserved to be examined under a microscope, the tubes lose their liquid and collapse, becoming hard to see, though there does appear to be a fuzzy edge on the organ slices when viewed under the microscope. Until now, those fuzzy edges had been written off as cracks that appear as part of the organ drying process. But, when a body is frozen, the tubes no longer collapse and can be peeled off the edge of the organ and seen with the naked eye.

Once you finally notice something that was always there, you can’t un-see it. We’ve likely all had experiences like that in life, like when someone tells you that two colleagues have been secretly dating for years, and you now realize you had noticed signs all along but yet still somehow missed it. This might happen in a company culture, where there have seen signs of toxic behavior for a long time, and it is not until a group of people decide to quit en masse that the leadership realizes it is pervasive. Sometimes it takes an ah-ha moment to open us up to the interconnections in our own systems that have always been there but we have overlooked. Now that we have this new view, we notice signs of it everywhere. How could we have missed this, you might be thinking? Yet, we do, especially when we have been trained to overlook things.

Neil Theise, who is created with this “discovery” not only practiced pathology, he taught it. He taught many students exactly what he was taught: “Those fuzzy edges? Don’t worry about them… they are just from the drying process” But they weren’t. They were the interstitium, something that he and his students looked at EVERY single day, and overlooked, again and again and again. Of course, now that they know better, they can’t un-see it.

Are there things that you are overlooking in the systems you care about? Things that might be so essential and so ubiquitous, that they are essential for connecting the whole system up, contributing to the emergent properties of the system you care about? Perhaps. What would it take to gain a new perspective to be able to see your own system with new eyes?

Sometimes the things we miss are HUGE, like super duper important. Remember, the interstitium was not only discovered on the edges of other organs but also connecting all organs together in a way that they can pass fluid through the whole body without going through the blood. Think about this for a second. How many times have you had your blood tested for information about your body? Western medicine has taught us to view the blood stream as the mirror of our health. Now that we know there is another entirely overlooked and separate system that our body can use to transport information and material between organs and beyond, without ever entering the blood, we might open up a whole new way of understanding and supporting the body system. For example, some scientists believe this may open up whole new ways of understanding how cancer spreads and how to treat it. By overlooking this body part, we may have overlooked one of the key components of human health and healing.

But here’s another layer of this story of “overlooking.”

When Theise and other researchers first published a paper about the interstitium, they held a question and answer session, and the first person they called on happened to be a Chinese medicine expert who noted, “In Chinese medicine, we’ve known about this for over 4,000 years.”

Touché.

THE LESSONS

Why did Western medicine, until now, overlook something that Chinese medicine and acupuncture have known about and taught about for thousands of years? And once again, how did we miss this important body part that is visible to the naked eye? To me, this very very late “finding” by Western medicine, or better yet, very very long missing, is a systems story, one that helps illustrate a lot of why systems understanding is so very important.

I teach systems understanding in universities, businesses, and organizations that are thinking about how they might shift the conditions that are holding the systems around them in place. When I learned about the interstitium, the first thing I thought was “This is an incredible systems story!” And it is. It is also a perfect illustration of the dangers of overlooking systems thinking skills and why systems and complexity understanding are so important.

From a systems understanding perspective, I believe these systems concepts can help us understand how the interstitium has been overlooked for so long, even with modern technology that allows us to see things at fine-grain resolutions. These eight concepts that were overlooked, and the lessons they reveal, might help each of us avoid overlooking the “interstitiums” in our own work: the obvious things that go unnoticed because our perspectives, approaches, biases, and culture prime us to overlook them.

1. Focusing on the whole, including relationships, not just the parts.

Dissecting involves cutting body parts out and separating them to examine them individually. This focus on parts vs. the whole is reflected not just in how we study them but who studies them. Doctors, and even ultrasound technicians, often specialize in one part of the body: the lungs, the heart, the uterus, etc. This specialization on “parts” goes beyond the medical field: academics specialize in one area of research (and there are many examples of academics discrediting each other’s work simply because one has tried to step out of their own field and look wider).

As noted, systems can’t simply be broken up into parts to be understood, and though the dissecting process and can teach us a lot, we also need expertise in the system as a whole (the body in this case) and, as all systems are embedded in other systems, we also need to look at the body within wider systems (i.e. the human as part of nature: including soil, air, water quality, etc). You might get a breast exam and find cancer, and then spend so much time focusing on the breast tissue, but overlook inflammation in your jaw from a poorly extracted wisdom tooth that might be contributing to that cancer as the inflammation moves down your body through your lymph (or, perhaps, through your interstitium). You might be focused so much on trying to improve school math tests results by focusing on teacher training, and overlook the other factors in the wider families, community, and school system that are contributing to those test results.

The interstitium was likely missed in part because it appears to be a network that connects ALL organs, and no one doctor or researcher was looking for these specific interconnections. It was missed, like the relationships between different parts of our social system are sometimes overlooked, when we look at pieces in isolation. By looking at the parts rather than the things that connect them, we often miss the emergent qualities of the systems as a whole.

Reflection questions: In terms of the problems and system(s) that you care about, can you think of any interstitiums that are overlooked when people focus on the parts, or the actors, in isolation? How are those interconnections and relationships impacting the issues you seek to see changed?

2. Honoring and embracing Indigenous ways of knowing.

Western medical scholarship has largely confirmed the efficacy of acupuncture for a range of maladies, but wasn’t necessarily able to “prove” why it worked, with some people deeming it a placebo effect and others recommending it even with a dearth of Western scientific evidence. Western dominant culture often values scientific “discoveries” over Indigenous knowing. By overlooking Indigenous and non-western ways of knowing, we are overlooking thousands of years of insight because it doesn’t fit a certain box of how knowledge is hypothesized and either confirmed or debunked.

Systems thinking invites us to take in information from many sources and perspectives and welcome a range of ways of knowing. It invites us to think more broadly about how knowledge comes into being, and how it is interrogated and spread. It invites us to ask new questions: if we know something works (i.e. acupuncture), but we don’t know why, what might we be overlooking or wrongly holding onto as “fact” that we might need to reconsider? In this case, Indigenous ways of knowing the body were overlooked and ignored, even when the evidence was right before our eyes. Where else is this happening? Where might this be happening in your field of work?

While ignoring Indigenous knowledge can clearly lead to missed learning opportunities and a widening of perspective about how “truths” are discovered, another common harmful practice is the taking of Indigenous knowledge and then calling it our own, which Western medicine is also guilty of. Currently, a friend of mine, biodynamic craniosacral therapist, Angela Richardson, is working alongside colleagues to honor and correctly cite the Shawnee Nation and their influence on Andrew T. Still, the founder of Osteopathic Medicine. Within the biodynamic craniosacral community there is an emerging conversation where a small group of senior teachers and practitioners are questioning the Shawnee influence on their practices. Some members of the community are advocating for the history to be taught simply with European roots, while Angie and others point out that credible and growing documentation clearly connects the origins of Osteopathic Medicine with the Shawnee people.

When we overlook Indigenous ways of knowing, or overlook the histories of our knowledge, we are not only causing disrespect and harm, but we are also overlooking parts of the system story, parts that are important for our understanding of the whole. In cases of complexity, there is never one root cause (imagine a tree with only one main root!), and never one contributing piece of knowledge. It’s complex, so we can’t expect to always get our histories or citation practices completely correct as some contributions might be collectively overlooked or unknown, but systems understanding and mapping practices invite us to try by expanding our aperture wider to look at interconnections beyond a simple linear story of cause and effect.

Honoring Indigenous knowledge invites us to listen more, ask more questions, and honor learning from many perspectives, even those that don’t fit our current ways of knowing. As this story shows, the Indigenous wisdom and ways of knowing, that contributes to acupuncture teaching and beyond, have been known for over 4000 years, and Western medicine dismissed it, only now to “discover” it more than a little late.

Reflection question: Are there perspectives, or ways of knowing, Indigenous or otherwise, that are overlooked or dismissed in your sector? What would it take to open up to listening to and exploring those perspectives, and what might be gained from such a pursuit? Are there perspectives whose origin stories are not adequately shared, where Indigenous origins or contributions are intentionally being obfuscated? Is there something you want to do about that?

3. Surfacing paradigms.

The paradigms, or mental models and patterns, through which we see the world, shape our beliefs and our actions. In Roger Martin’s book, “A New Way to Think” he speaks to the impact paradigms have on how our companies and organizations are run. At the start of the book he gives an example of a business trying to incentivize innovation in their company. Their mental model about innovation was something like this, “Identifying innovative ideas requires using data to vet which ideas are most likely to succeed. If we vet well enough, we’ll find the most successful innovations.” This company was seeking innovations that were outliers, with the ability to bring in great change and great finance, but they kept only getting incremental innovations, not transformative ones. So, like so many of us, they decided to apply their mental model even more rigorously vetting harder and harder, and getting worse and worse results.

Martin points out that, when something isn’t working, we often assume it is because we haven’t applied our mental model correctly, not that our mental model is flawed. In this company’s case, it was indeed flawed, and applying it more rigidly was pushing their results in the opposite direction of their goals. Martin points out a flaw in their thinking: that using existing data to verify the potential of an innovation is only going to get you incremental change, because those changes are the only things with data to back them up, whereas the real potential outlier innovations are so far removed from the current reality, that there wouldn’t yet be data to verify them. No matter how “correctly” that company vetted the data, they were never going to get where they wanted to go, like sprinting and taking shots at the wrong goal is never going to lead to winning a game. In linear action, we can set our sights on a goal and race towards it, and our rate of success will simply depend on how fast we move. In complexity, when things aren’t linear, we might get where we want to go “faster” by slowing down to reflect on our mental models, and the lay of the land of the systems in which we work. Once we have better understood the system and where we might want to head, we can put those “efficiency” and “speed” skills of the linear model to use, oscillating, like the Mahayana Buddhist symbol of a vajra, in a balance between learning, and action.

Reflection question: What are the thoughts, beliefs, and mental models that are driving your work? Which are assumptions, and which are facts? Like a limiting belief holding you back in your personal life, what limiting beliefs or perspectives might be holding your work back? Where might it make sense to pause and reconsider your mental models rather than plow ahead harder and faster with your current ones?

An image of a vajra, which we described in the book “Learning Service” using a definition gifted to my friend and co-author, Claire Bennett, by a monk in Nepal: “Action without learning is ignorance. Learning without action is selfishness.” Image by © Nndanko | Dreamstime.com

4. Building the power to transcend paradigms.

The late Donella Meadows, a famous systems author and educator, ranked different types of leverage points in increasing order of effectiveness. According to her ranking, the “deeper” leverage points are more effective levels from which to impact change, though of course they are also often more difficult to change. One of the “deepest” leverage points she identified is changes to “the mindset or paradigm out of which the system — its goals, structure, rules, delays, parameters — arises.” As we just discussed, changing our beliefs about something, or our beliefs about what is possible, unlocks so many other changes in how we might act, and when that happens at the collective level, huge change is possible.

As my friend and co-author, Claire Bennett, pointed out in our book, Learning Service, we often blame people when they “change their mind” when in fact perhaps we want to be celebrating people for holding their perspectives lightly and instead change our vocabulary from “changing your mind” to “forming new perspectives based on new information.” If we want to see more flexibility in how people think, we might want to celebrate the ability to change mental models, not vilify it.

According to Meadow’s framework, “There is yet one leverage point that is even higher than changing a paradigm. That is to keep oneself unattached in the arena of paradigms, to stay flexible, to realize that NO paradigm is ‘true,’ that every one, including the one that sweetly shapes your own worldview, is a tremendously limited understanding of an immense and amazing universe that is far beyond human comprehension.” She calls this deepest leverage point “The power to transcend paradigms.”

I am only just beginning to understand what she meant, and the interstitium has been one of my teachers in this process. Roger Martin’s work has been a teacher too. Even though his work is often focused on companies and mine on broader social impact work, his lessons are such an important reminder that surfacing our mental models and recognizing our ability to change them is an, if not the most, essential tool for creating change. In these complex times we are in right now, I am reminded of this lesson. I often hear people on different sides of polarizing political divides argue “We just need to ‘fight harder’” and I think, is that true? In what paradigm does fighting harder and harder deescalate a divide?

The interstium story invites us to reconsider which paradigms are serving us, and which are really just limiting beliefs. And once we shift a major paradigm, it becomes even easier to notice that all of our other decisions are also being shaped by paradigms, which we can continue to choose, or hold lightly, ready to shift them if we come across new information that invites us to do so.

Reflection question: When was a time you were able to significantly shift a mental model, and what happened because of that? Are there any mental models that you know are holding your back? Any that are holding back progress in the work that is happening in your system? Any that you believe are holding back humanity? Any that you want to change? If yes, what do you want to start doing about that?

Psst. Ever heard of the Ladder of Inference:

This image of the “Ladder of Inference” is from the Waters Center for Systems Thinking in their free Thinking Tools Studio which has a TON of great resources. Plus they have a fabulous Advanced Facilitator Credentials program - which I am in now and loving - for anyone who wants to up their systems thinking and teaching skills. waterscenter.org

(If you aren’t already familiar with the Ladder of Inference, I highly recommend you check out the Waters Center for Systems Thinking free online resources about it in their Thinking Tools Studio. I wont get into the details of it now, but suffice it to say it’s a concept we should all know about illustrated in a pretty little ladder form: our beliefs, or mental models, shape what we notice in the world, thereby reinforcing our existing beliefs. In other words, as Richard Wiseman tried to prove in his work around trying to teach people to be lucky in his Luck School, if you think you are lucky, you find evidence for that all around you, and if you think you are unlucky, you find evidence for that all around you too. Therefore, what you believe matters, and also your ability to look beyond your beliefs, as a way to then reshape those beliefs, matters even more. Hence, the power to transcend paradigms.)

5. Examining and learning from the outliers (not vilifying them or shoving them under the rug).

It’s hard for us to take in new information when it conflicts with our current beliefs, especially when the new information conflicts with our deepest mental models. When something challenges our core “truths,” many of us tend to plug our ears and flight back rather than listen to the things that might make us question our deepest mental models.

In Donella Meadow’s piece on leverage points she shares that she believes people are often pushing leverage points in the opposite direction of where they want to go, like in the company Roger Martin was exploring. Sometimes it’s hard to embrace the fact that the work you are doing might be causing more harm than good, especially when it challenges your core beliefs. As a society, this skillset of being open to learning from the outliers, even when they contradict our views, is something we could benefit from working on if we want to catalyze the systems change we need to collectively thrive into the future. Unfortunately, what often happens is, instead of listening to, learning from, and designing deeper questions based on the outliers that don’t fit our mental models, we vilify them, make them wrong, and then ask the outliers to prove that “they” are right, rather than using the fact that those outliers exist as a means of questioning what might not be right about our own models.

As a society, we do this with so many topics. We vilify someone as a “conspiracy theorist” when they believe one thing we don’t like, and write off any other research or opinions they might have. We do this with people who voted for “the opposition” – whatever that means to you – as if the way someone votes might give us a right to not only plug our ears but also vilify everything else about them. We do this whenever someone tries to challenge mainstream beliefs.

Take The Telepathy Tapes, a very popular podcast series about non-verbal autistic children. (If you haven’t listened to it yet and you care about systems change, mental models, and what it takes to challenge the status quo, I highly recommend it.) The series shares the story of dozens of parents, teachers, therapists, and researchers who have noticed patterns that show that the non-verbal autistic children in their care seem to be communicating non-verbally. The podcast name alone is so off-putting for some, as they immediately start thinking of things like Star Trek, and they write the show off as garbage. In fact, many of the more public critiques of the series do exactly what modern culture usually does with outliers: vilify the messenger rather than listen to and ask questions about the message and the data it is sharing. The producer’s character is questioned, her “expertise” is trashed, and the onus of “proof” that telepathy is what is going on with these children is pushed back on the messenger.

Instead, what would it look like to listen, and even if we aren’t sure telepathy is what is happening, what would it look like to take in the challenging facts she is sharing and ask what those facts might mean about our on mental models. In this case, a key indisputable fact the producer is presenting is that not just one or two or a few dozen, but thousands of people, mostly women (mothers, teachers, therapists) are stating that they are being silenced and that, some for 50+ years, they have been trying to share their research that their children are somehow communicating without words. They too don’t know the means, and they too want to know more, but rather than being listened to, and having their research studies examined, they are being vilified and discredited before their stories are even heard. This is what we do to people when the evidence they are presenting challenges our deepest beliefs - we make them wrong, evil, or dumb, before even listening.

How many others, before Neil Theise, might have seen pieces of the interstitium and had questions about it, but didn’t take their research further when they were laughed at, ignored, or criticized? What do we miss out on as a society when we silence voices that are questioning the dominant narrative? One thing we get is polarization, like the times are in now, and if those actions got us into these problems, shifting them might help us get out.

Reflection question: Whose voices are you silencing, in your work, or in your head, in order to not have to deal with the threat of potentially needing to re-examine your own beliefs? What impact does that have on you, on them, and on the world?

6. Remembering science is hypothesis, not fact.

In recent years, the term “science” is being abused. People throw out insults like “They don’t believe in science!” or “Look up the science” as if science were about facts. By definition, science is about hypothesis, experimentation, theories, and predictions. Questioning assumptions is essential to good science. When we get so stuck in thinking our hypothesis is a “fact,” we can completely ignore something right in front of our eyes and be very righteous or resistant to change when new information comes along. In systems work, we look at the mental models or paradigms that are holding a system in place, and if we can really embrace Donella Meadow’s message, we hold those paradigm’s lightly enough to be open to new information, even if it might challenge our current hypothesis.

Reflection question: Are there any current hypothesis you have about your work that you have been unwilling to reconsider, even in the face of opposing views? Are there any “righteous” behaviors you, or others in your system, have been engaged in with regards to dominate beliefs? Is there anything you want to start to hold more loosely and/or any other opinions you want to listen to in order to expand your own thinking? Where might the current science, or mainstream opinions, be wrong in your field?

7. Embracing a beginner’s mindset and practicing presence.

Dr. Neil Theise shared this powerful insight about how his mindset might have contributed to his success at helping to identify the interstitium when so many others had overlooked it: “My Zen [Buddhist] practice is about cultivating beginner's mind, to just be witness to the present moment and not attached to preconceived notions, not anticipating what you think you know will happen. My practice of pathology uses the same method, which is probably not a coincidence.” Cultivating mindfulness and practicing presence may not just be a way to preserve our mental health or stay calm in turbulence, but it is also a key to noticing what is true. What is true right now? If you asked that question about the work you are doing, and could take off the well-earned lens of your historical knowledge that you wear every day that color the world with your life experiences and mental models, what would you see? Systems understanding helps us ask “What are we overlooking because we are not really present to the current reality?”

Reflection question: Are there any problems you are currently facing in your work that might benefit from a fresh look? How could you go about recreating the beginner’s mindset in your own view of the problem, and/or how could you go about bringing in perspectives to re-look at old problems in a new light? If you don’t yet have a mindfulness or meditation practice, and it’s something you are curious about, why not give it a try?

8. Overcoming cognitive dissonance and group think.

I am not sure if it is human nature or centuries of human culture that compel us to only see or seek out “facts” that support our hypothesis. This limited view is certainly exacerbated by social media and news filters with algorithms that tend to confirm our existing biases and beliefs. That said, it is hard enough to even consider that our beliefs might be wrong, let alone to speak up about them when we worry about the judgement of others. Change, like the potential change the interstitium “discovery” brings to Western medicine’s understanding of the body, requires us to speak up when something needs questioning. That is hard to do in a cancel culture world, but if we let the “speaking up” muscle atrophy, we are really going to be in trouble as a species.

Speaking truth to power, pointing out the flaws in collective logic, and speaking up when something is wrong or unjust is not only a super power, but an essential component of collective human thriving (even though it might not result in immediate thriving for those brave enough to speak out in the moment). As such, leadership training and support to identify and speak up when we come up against cognitive dissonance might be one of the most important tools we can teach.

For example, the teachers interviewed in the Telepathy Tapes podcast who noticed that their students appeared to be sharing information non-verbally needed to first get over their own internal cognitive bias, a belief that this was impossible, and then had to be brave enough to speak up about them. In that case, some were removed from jobs, lost licenses, or are still speaking under pseudonyms, as they worry that sharing their reality in a culture with a dominant paradigm that rejects their findings can not only lead to ridicule but also harm. What would it take to listen to them as brave people and ask questions alongside them, instead of vilifying their courage and standing in opposition to them?

People putting themselves and their reputation on the line to ask questions about the current reality are often doing so to help us collectively learn, yet society often burns them at the stake, literally or figuratively. Questioning our biggest underlying collective mental models, like materialism, can clearly lead to violent push back, but not all speaking up needs to be approached with the same fear. Building the muscle of speaking up can start with the small things: speaking up when you hear people collectively speaking ill of someone and you know the story is one-sided, speaking up when you hear people say change is “impossible” and silencing new ideas, or any other number of smaller opportunities to use our voice to speak up against limiting beliefs, injustice, and false or incomplete “facts.”

I was recently at a conference with Kesho Scott, a recently retired professor from Grinnell College, who noted that one of the key human skill-sets she thinks we need to foster in these times is “learning to survive other people’s disapproval.” I couldn’t agree more. As an educator, I wonder: how do we prioritize teaching the ability to be with the disapproval of others? Who is doing that well? How can we ALL incorporate that into our teaching, no matter what the official topic of our course is? I certainly plan to learn from the likes of Kesho Scott and try.

Reflection question: Is there anything you have felt compelled to speak up about that you have silenced in yourself out of fear of ridicule or worse? What potential are you holding yourself and those around you back from through your silence? How can you work on building this muscle up in your life and in your teams?

WHAT ELSE ARE WE MISSING?

The “discovery” of the interstitium is a scientific breakthrough, which was always right before our eyes. This “innovation” in how we understand our bodies, and how we might go on to treat cancer and other diseases, was only possible because scientists, like Dr. Theise, were thinking in systems. They had to be present to the reality in front of them, look at the whole and relationships beyond the parts, be willing to challenge scientific hypothesis, go against dominant cultural paradigms, and overcome cognitive dissonance. In doing so, they are helping to prove that in this case, and likely many others, Indigenous ways of knowing might be more “advanced” than our modern ways.

At the end of the Radiolab podcast, Dr. Theise gets a little emotional. He notes that for over 30 years he has been teaching budding scientists that those cracks you can see on the slide at the edge of the organ are just part of the drying process. But, as we now know, they aren’t. They are the interstitium, something he looked at nearly every day but overlooked. He asks “What else have I been teaching incorrectly that is right in front of my eyes?”

We could probably all benefit from asking ourselves that question: What do we “know” about the systems we care about that might be wrong? What are we teaching others to view incorrectly? Systems thinking and embracing complexity invites us to step off our high horses and acknowledge our limited knowledge more often. The answer to so many questions is really, “It’s complex,” but we often default to binary answers—right or wrong, black or white, good or bad. No, it’s complex.

The people we think are wrong might help us see where we aren’t yet right. If we can’t listen across divides, reconsider our paradigms, and begin to see the truths we’ve overlooked right in front of our eyes, we might miss some of the most important opportunities we have to contribute to changing the systems around us.

The interstitium story shows the value of systems understanding and asking what might feel like difficult questions. If we can all incorporate these principles into our own work, and speak up when something doesn’t make sense, we might be able to get unstuck collectively, and goodness knows we are in time of big stuck-ness right now. May this article and these principles be useful for you as you do your part in contributing to the collective change we are in, and may you speak up when you see something we have collectively missed, even when it was right in front of our eyes. We need you, as those people questioning the mainstream narratives on complex challenges are the ones who are going to help us break out of our limiting beliefs about ourselves and the world and move us all towards more collective thriving.

Note: When my friend Corey first sent me the Radiolab podcast episode about the interstitium, I got that electric feeling in my body when I know I am learning something really important. I could tell this was going to have a huge impact on how we collectively thought about health, but I knew it was also going to impact how I thought about systems and the urgency of the work I care about. I wrote to my colleagues, Anna and James, as we were working on two books about systems (one of which recently came out and can be found here: The55minutes.com) and said “Oh my goodness, this is such a great story about the value of systems understanding!” I couldn’t wait to write this piece as to me it felt like such a great illustration of the work we care about. This article is adapted from a second book that came out of our work together which will hopefully be coming out later this year. Credit for some of the thinking in this article goes to both Anna and James.

Fascinating!

Absolutely fabulous piece, Daniela, that weaves so many important elements of systems thinking and complexity together - all through this fascinating narrative. Thank you!